Mutations of the INAVA gene may boost the risk of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), according to a new study whose findings not only explain the pathological mechanisms underlying IBD, but may also help design new therapies for patients with such mutations.

The study, “An inflammatory bowel disease-risk variant in INAVA decreases pattern recognition receptor-induced outcomes,” appeared in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

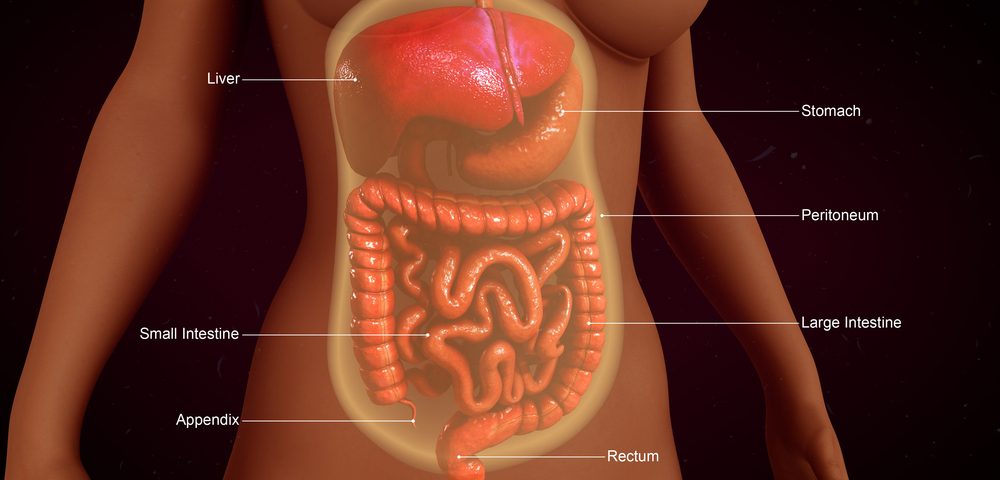

IBD is triggered when the immune system mistakes the body’s own microbes, food and other materials for foreign bodies and attacks the intestine, causing inflammation and damage. This faulty immune system also fails to recognize invading bacteria, affecting intestinal activity. Genetic alterations and environmental factors may cause this weakness; indeed, several genes have been linked to IBD.

One such gene is INAVA, but its exact contribution to this disease remained unknown. The INAVA gene encodes a previously unknown protein with the same name, which is expressed in human intestinal cells.

In their study, a Yale University research team led by Clara Abraham stimulated cells from the intestines and blood of healthy people with bacteria or bacterial components, to understand how the INAVA protein works. Under these conditions, they observed, intestinal cells produce normal levels of this protein, which is required to initiate a molecular mechanism that clears bacteria.

However, cells carrying mutations within the INAVA gene produced lower levels of the corresponding protein. Loss of INAVA reduced the immune system’s cells capability to detect bacteria, stimulate the production of inflammatory molecules and trigger molecular signaling pathways aimed at eliminating the pathogens.

These results led researchers to believe that mutations leading to decreased expression of the INAVA protein (also known as “loss-of-function” mutations) increase the risk of IBD.

“Taken together, these results identify a role for a previously undefined protein encoded by [the] INAVA [gene] and establish clear roles and mechanisms for the protein in regulating [bacteria-triggered] outcomes, as well as establishing loss-of-function consequences for the IBD-associated risk variant in this gene,” the study concluded.