A team of researchers at the University of California, Riverside, found that a tight control of the levels of two forms of the same protein, hepatocyte nuclear factor 4-alpha (HNF4-α), is critical to prevent intestinal diseases. The findings are described in the study, “Opposing roles of nuclear receptor HNF4α isoforms in colitis and colitis-associated colon cancer,” published in the journal eLife.

The HNF4-α gene has been linked to several gastrointestinal disorders, including colitis and colon cancer. A mutation in a single nucleotide in HNF4-α has been associated with ulcerative colitis. However, there are two variants of this protein, P1-HNF4-α (P1) and P2-HNF4-α (P2), and the role of each variant in normal and malignant colon function is not known.

Researchers, led by Frances M. Sladek, a professor of cell biology at UC Riverside, studied the role and distribution of both isoforms, and found that a tight balance of P1 and P2 is critical to reduce the risk of colitis and colon cancer.

“P1 and P2 have been conserved between mice and humans for 70 million years,” Professor Sladek said in a press release. “Both isoforms are important and we want to keep an appropriate balance between them in our gut by avoiding foods that would disrupt this balance and consuming foods that help preserve it. What these foods are is our next focus in the lab.”

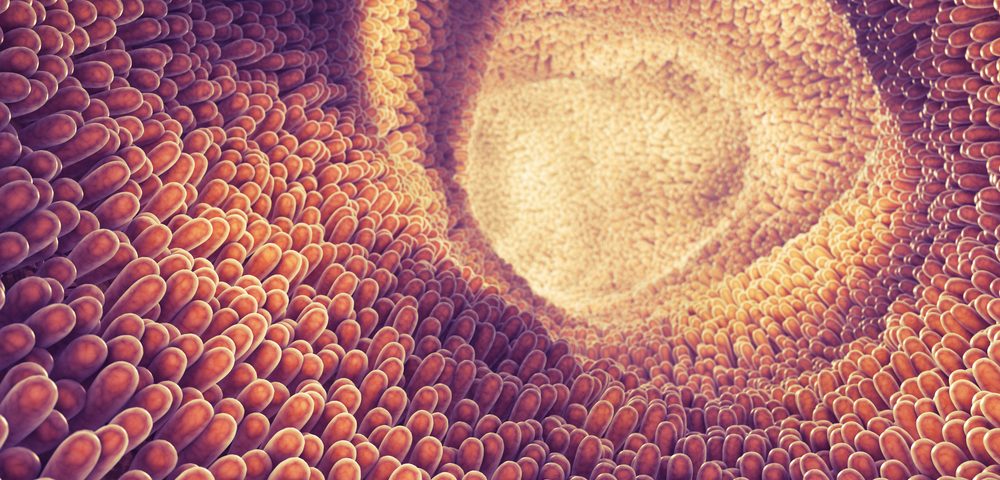

Although HNF4α is expressed in the liver, kidney, pancreas, and stomach, the intestine is the only adult tissue that expressed both P1 and P2 isoforms. Professor Sladek and his lab showed that whereas P1 is expressed primarily at the differentiated compartment of the finger-like structures found at the colon surface, P2 is found in the proliferative compartment, where the stem cells that renew the intestinal epithelial tissue every three to five days reside.

Using genetically engineered mice that expressed only one of the isoforms, and exposing them to a carcinogen followed by an irritant that stressed the colon epithelial cell lining, the researchers found that P1 mice had less tumors than control mice, whereas P2 mice had more tumors than the controls. Furthermore, when the mice were exposed to the irritant alone, P1 were resistant, whereas P2 were much more susceptible to develop colitis.

Investigators explained their results by perturbations in the intestinal barrier. P1 mice had an enhanced barrier to prevent bacterial infections, whereas P2 had a compromised barrier function. In fact, when the research team examined the expression of genes in P1 and P2 mice, they found that P2 mice had much higher levels of RELM-beta in the intestine, a molecule that modulates the immune system and which has been implicated in colitis.

“This makes sense since a reduced barrier function means bacteria can go across the barrier, which activates RELM-beta,” Professor Sladek said. “We also found that the P2 protein transcribes RELM-beta more effectively than the P1 protein.”

The team’s next goal is to understand how diet can affect the distribution of P1 and P2 in the gut.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract that affect more than 1.6 million people. Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are the two most common types of IBD. Patients with ulcerative colitis have an increased risk of developing colon cancer.