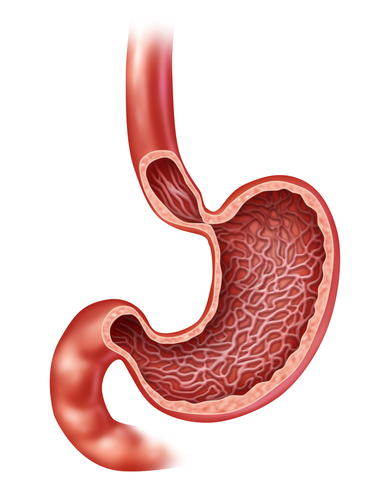

Scientists recently made a significant breakthrough in the field of gastroenterological research and development by successfully creating the first three-dimensional human stomach tissue, which can serve as a miniature stomach model to aid more comprehensive studies into the development of diseases, and ultimately change how treatments are developed and how public health crises are addressed.

Scientists recently made a significant breakthrough in the field of gastroenterological research and development by successfully creating the first three-dimensional human stomach tissue, which can serve as a miniature stomach model to aid more comprehensive studies into the development of diseases, and ultimately change how treatments are developed and how public health crises are addressed.

Lead investigator Jim Wells, Ph.D., is a scientist at the division of Developmental Biology and Endocrinology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. He and fellow researchers explained in their report in the journal Nature, dated October 29, 2014, that the achievement was made possible by human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs). Together with other investigators from the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, they were able to create gastric organoids or “mini-stomachs,” which facilitated further study on H. pylori infections — one of the primary causes of peptic ulcer disease and stomach cancer.

Through this new development researchers will be able to model and examine even the earliest stages of cancer and study how it can be a factor in obesity-related diabetes. This milestone proves the possibility of utilizing hPSCs in generating other organ tissues and organoids as this study has also laid the technical groundwork for generating 3D tissue with complex architecture and cellular composition. Soon, scientists will have human-based organ models that would provide more accurate information compared to studies performed on laboratory mice.

As for the collaborative study on induced H. pylori infections on these lab-generated organoids, the researchers observed an impressively rapid bacterial proliferation in stomach epithelial tissues. In 24 hours, they were already able to note biochemical changes in the organ, including the activation of a cancer gene.

The scientists behind this scientific milestone had to make-do with the little literature on embryonic stomach development, but they were able to mimic these steps in a petri dish. In a month, the stem cells were able to create a 3mm (1/10th of an inch) gastric organoid. Wells and his team are confident this new knowledge of how a stomach is formed will eventually lead to bigger discoveries on anatomical, cellular and genetic faults that predispose a person to disease.