Early-onset of the severe inflammatory bowel disease ulcerative colitis may be caused by several genetic factors, according to a recent study conducted at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). The research performed with mice suggest possible new targets for prevention and treatment options to address the inflammation caused by the early onset of the rare disease that affects infants and young children and can lead to colon cancer and increased risk of liver damage.

Early-onset of the severe inflammatory bowel disease ulcerative colitis may be caused by several genetic factors, according to a recent study conducted at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). The research performed with mice suggest possible new targets for prevention and treatment options to address the inflammation caused by the early onset of the rare disease that affects infants and young children and can lead to colon cancer and increased risk of liver damage.

In collaboration with the Pusan National University in South Korea, scientists from the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA designed a first-of-its-kind animal model that mimics early-onset ulcerative colitis and can be used to test investigational drugs for the treatment of the disease. The results of the collaboration between universities was published in the Gastroenterology journal.

“We hope that identifying these key genetic factors and providing a unique research model will help lead to new approaches to treat early-onset ulcerative colitis, a devastating disease that currently has no cure,” said the study’s senior author and associate adjunct professor of medicine in the Division of Digestive Diseases at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Sang Hoon Rhee.

Based on other studies that revealed the importance of the anti-inflammatory protein interleukin 10, which refrigerates the inflammatory responses in the body, and is lacking in people

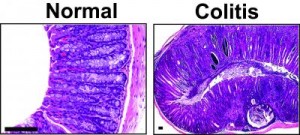

Credit: The journal Gastroenterology/UCLA

with early-onset ulcerative colitis, scientists analyzed genetic information. “We knew that interleukin 10 played a role,” explained the assistant professor at Pusan National University’s School of Pharmacy and the study’s first author, Eunok Im. “But recent clinical and experimental evidence indicated that in addition to this protein’s crippled action, there may be other genetic factors at work causing early onset of this disease.”

The team concluded that phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN), a protein that contributes for the cells growth and communication, among other functions, might also work in together with interleukin 10 and propitiate the ulcerative colitis development. Mice who registered lower levels of interleukin 10, also showed a greater loss of the PTEN gene in the intestine causing extensive inflammation, severe colitis and colon cancer at early ages, and developing symptoms and early-onset ulcerative colitis in a similar way to humans.

The PTEN loss in the intestine also interrupted the antibacterial activity and altered the colon’s bacterial diversity, registering a substantial increase of the bacteria Bacteroides, the one responsible for triggering massive inflammatory responses that cause various inflammatory diseases. The research team was able to block its ability to do this by using genetic and pharmacological interventions, and observed a large decrease of the number of early-onset ulcerative colitis in the mice. The scientists are now planning to perform further studies in order to evaluate the results on humans, as an eventual way of discovering new approaches to treat or prevent ulcerative colitis.

“Future study may help us better understand how this bacteria has the potential to elicit inflammation in the colon and explore the molecular mechanisms of how the bacteria impacts disease onset,” believes Dr. Charalabos “Harry” Pothoulakis, the other author of the study and a professor of medicine in the division of digestive diseases, who holds the Eli and Edythe L. Broad Chair in Inflammatory and Bowel Disease at UCLA and is the director of the UCLA Center for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases.