Researchers have found that the MDR1 gene helps protect immune cells from the damaging effects of bile acids in the intestine, preventing a condition known as ileal Crohn’s disease.

The findings from The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) in Florida suggest that blocking the action of bile acids in patients with a defective MDR1 gene may help halt the progression of ileal Crohn’s, the most common type of Crohn’s disease. Crohn’s is a form of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

The study, “The Xenobiotic Transporter Mdr1 Enforces T Cell Homeostasis in the Presence of Intestinal Bile Acids,” was published in the journal Immunity.

The T helper 17 (TH17) cells are a subset of immune cells that travel throughout the body to protect against infections. These cells, however, can also trigger chronic inflammation, especially in the intestine, promoting Crohn’s disease.

More insights into how Th17 cells adapt to each part in the body – for example, the environment in the lungs is different from that of the gut – would allow researchers to design better, more targeted therapies.

“We need therapeutic strategies that specifically target chronic inflammation in the gut, skin or other tissues, instead of just generally suppressing the entire immune system,” Mark Sundrud, PhD, lead author of the study, said in a press release.

Sundrud’s team hypothesized that Th17 cells may lead to the activation of different genes according to their body location – in the lungs they might activate a gene different from those in the intestine. In fact, they showed that when Th17 cells penetrate into the gut they activated a gene called MDR1.

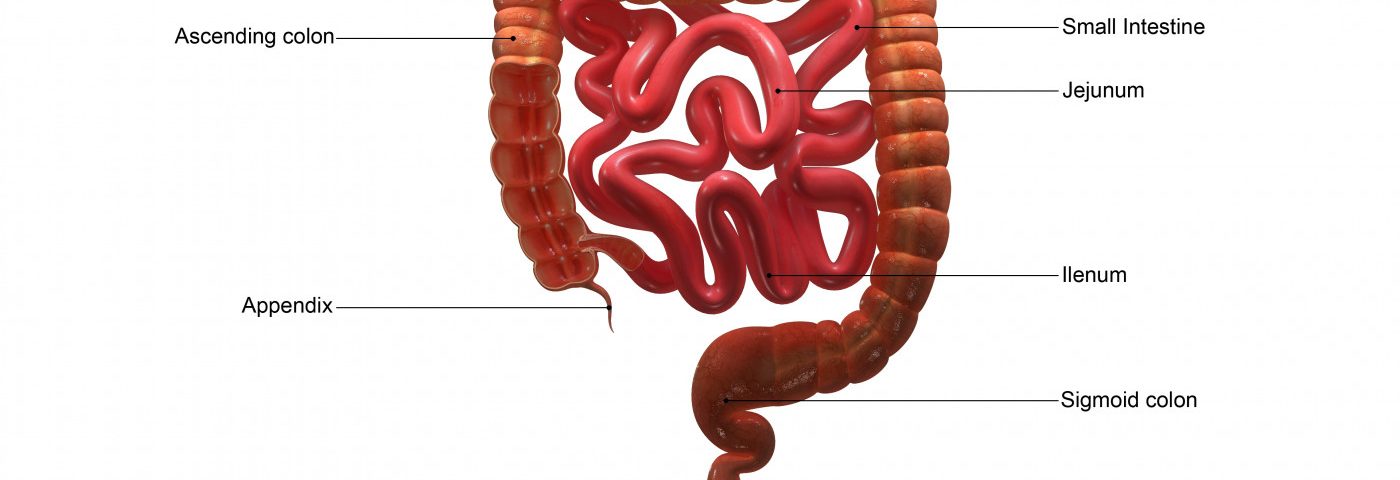

Now researchers have discovered that Th17 cells increase MDR1 as a defense mechanism against the acidic bile acids. After being released by the liver after a meal, bile acids are reabsorbed at the end of digestion in the ileum, the final part of the small intestine.

“T cells only see high levels of bile acids in the ileum. They know this, and they adapt once they get there,” Sundrud said.

Chronic inflammation in the ileum gives rise to ileal Crohn’s, the most common form of Crohn’s disease.

Th17 cells activate MDR1 in the ileum. Using mice genetically engineered to lack MDR1, researchers found that, in its absence, Th17 cells become susceptible to bile acids and undergo severe oxidative stress. This makes the cells hyper-reactive, triggering inflammation in the ileum, and ultimately causing Crohn’s disease.

They also found that blocking the reabsorption of bile acids in the ileum restored the equilibrium (or homeostasis) and functioning of Th17 cells, preventing ileal inflammation.

The significance of these findings in Crohn’s disease patients was confirmed when researchers found that a subset of patients with ileal Crohn’s disease have a defective MDR1 gene.

Overall, these results suggest that dysfunction of MDR1 may promote ileal Crohn’s disease due to the detrimental effects of bile acids. In these patients, capturing bile acids in the ileum may be an effective therapeutic approach, a hypothesis that Sundrud and his team hope to test in a future clinical study.