The mix of bacteria in the mucus lining the intestine begins changing long before symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) show up, according to a study in mice at the University of Manchester in England.

Spotting the transition as it begins could lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment of the disease, researchers said.

The study, “Compositional changes in the gut mucus microbiota precede the onset of colitis-induced inflammation,” was published in Inflammatory Bowel Disease.

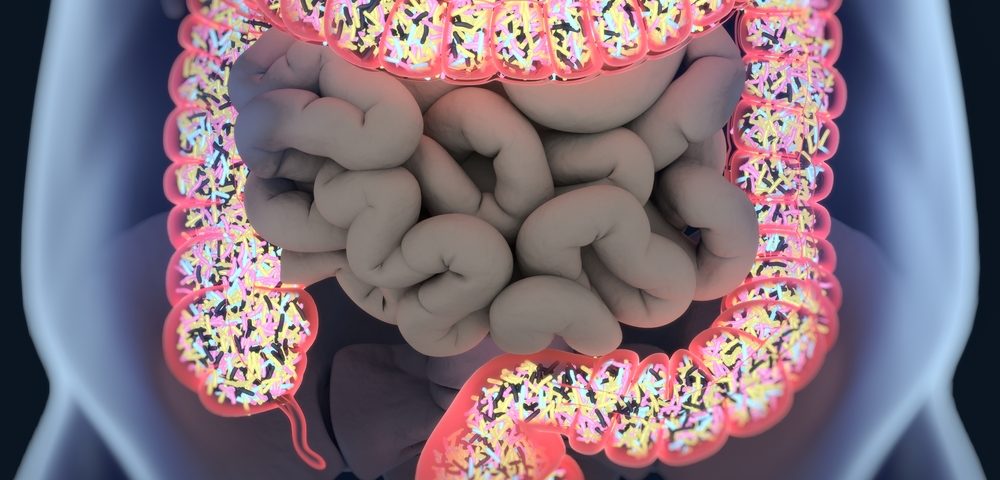

IBD involves inappropriate immune responses to the gut’s natural community of microbes, collectively known as the microbiome. The abnormal responses can cause chronic inflammation.

Typically, doctors are unable to diagnose the disease until symptoms emerge. Once they see symptoms, they look at stool samples to see if the microbe mix is different than it ought to be.

Because the analysis occurs only after a patient begins experiencing gut inflammation, a chicken-and-egg question that has long puzzled researchers is: Are the changes in the gut’s bacterial mix causing the inflammation, or are they the result of it?

The British researchers decided to look at changes in the gut’s bacterial mix before a person developed colitis, or inflammation of the inner lining of the colon.

They analyzed the microbe mix in both the mucus covering the gut lining, or epithelium, and in the stools of mice with IBD. The mucus plays a key role in protecting the lining.

The bacterial community in the stools was different from the community in the mucus, they found. More important, the change in the bacterial mix associated with IBD showed up in mucus but not in stool 12 weeks before bowel inflammation began.

Alterations in the microbial composition of the mucus were accompanied by physical changes, the researchers added: The mucus layer became much thinner.

“Stool samples do not fully replicate the complex picture of the microbiota in the gut which lives in communities in discrete locations within the gut,” Dr Sheena Cruickshank, the lead author of the study, said in a press release.

“We took mucus samples which are found right next to the cells of the gut and therefore closer to where the problems develop,” she said. “As a result, we could see changes in the microbiota 12 weeks before they were detectable in the stool samples.”

The results suggest that studying mucus bacteria early could help scientists understand how IBD develops.

“Being able to observe what is upsetting this balance earlier and understanding the bacteria involved will give us much greater opportunities to understand the causes of some of these painful diseases and better help patients,” Cruickshank concluded.