A bacteria-binding protein called ZG16 was found to be a key player in the gastrointestinal tract’s protective barrier, responsible both for controlling the resident bacteria population and for keeping them at a safe distance from the host. A lack of ZG16 in the gut of mice was shown to result in both inflammation and abdominal fat accumulation, according to a new research.

The study, “Gram-positive bacteria are held at a distance in the colon mucus by the lectin-like protein ZG16,” published in the PNAS scientific journal, provided new information as to how the human body can be affected by, and respond to, the large quantities of bacteria commonly found in the gut.

“The hope is that eventually, we’ll be able to administer this protein to improve protection against bacteria in patients with a defective barrier,” Joakim Bergström, the study’s lead researcher, said in a press release.

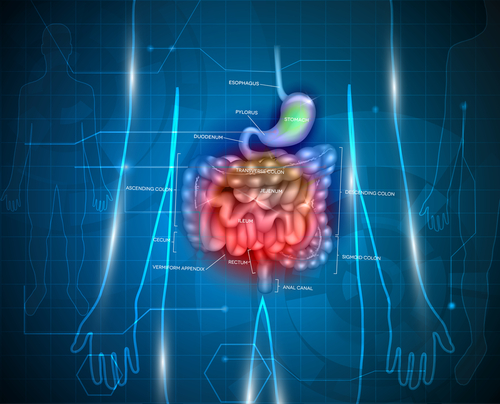

A mucus layer protects the body from gut bacteria, composed of proteins produced by specialized cells (goblet cells) that separate intestinal bacteria from the surface of the intestine. This is the first protective barrier that stops resident intestinal bacteria from harming tissues or causing inflammation.

The research shows that the ZG16 protein, working together with the protective mucus layer, could bind and aggregate bacteria, clumping them so as to prevent them from reaching and penetrating the intestinal wall.

Animal models that lack this protein have a defective a mucus layer, one that allows bacteria to pass the intestinal wall and move into the body. This breach induces low-grade inflammation in tissues, in accordance with a bacterial infection immune response. Mice without the protein in the study also had greater abdominal fat.

“ZG16 is important for a safe normal host-bacteria symbiosis as it does not kill commensal bacteria, but limit bacterial translocation into the host,” the researchers said.

The research provides new insights into the process involved in inflammatory bowel diseases and, more generally, into diseases such as obesity and inflammation.

“It’s becoming very clear now that a significant amount of bacteria leaks through the intestine into the body, which plays a role in inflammatory diseases, and even obesity, at least in mice. This indicates a principle that is probably quite universally applicable,” said Gunnar C. Hansson, the study’s senior researcher.